In the 150 years since Darwin published Origin, those "important researches" have produced results he could never have anticipated. He could not have been more right-evolution is quite simply the way biology works, the central organizing principle of life on earth. "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution," the pioneering geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky titled a famous essay in 1973. Since then, even the most unanticipated discoveries in the life sciences have supported or extended Darwin's central ideas-all life is related, species change over time in response to natural selection, and new forms replace those that came before. "In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches," he wrote in Origin.

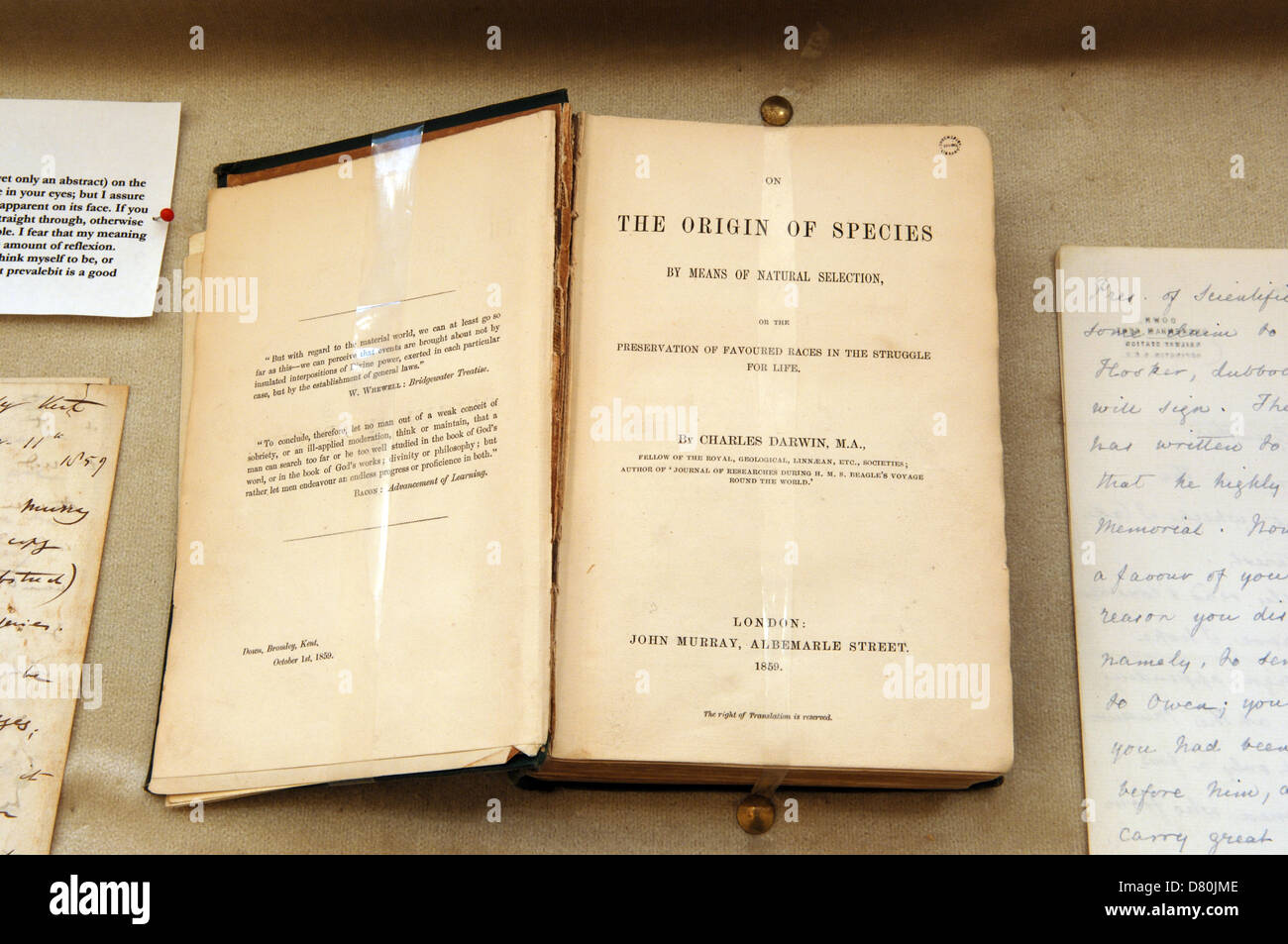

But Darwin recognized that his work was just the beginning. Perhaps because of that remarkable success, "evolution," or "Darwinism," can sometimes seem like a done deal, and the man himself something of an alabaster monument to wisdom and the dispassionate pursuit of scientific truth. It also survives as a model of logical thought, and a vibrant and engaging work of literature. Today, Origin ranks among the most important books ever published, and perhaps alone among scientific works, it remains scientifically relevant 150 years after its debut. " Cuidado," he wrote in another notebook around that time, using the Spanish word for "careful." Evolution was a radical, even dangerous idea, and he didn't yet know enough to take it public.įor another 20 years he would amass data-20 years!-before having his idea presented publicly to a small audience of scientists and then, a year later, to a wide, astonished popular readership in his majestic On the Origin of Species, first published in 1859. And it was as if he had an inkling of the upheavals to come as he pored over specimens he had collected and others had sent him: finches, barnacles, beetles and much more. In South America, Oceania and most memorably the Galápagos Islands, he had seen signs that plant and animal species were not fixed and permanent, as had long been held true. He'd recently returned to England after his five-year journey as a naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. Charles Darwin was just 28 years old when, in 1837, he scribbled in a notebook "one species does change into another"-one of the first hints of his great theory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)